Gianluca Costantini before a gigantic reproduction of his Patrick Zaki drawing in Bologna

We are pleased to open this year with an interview with an artist and an activist, Gianluca Costantini.

For those who do not know him, Gianluca Costantini is an Italian cartoonist who has taken part in many human rights campaigns and used his artistry to speak up for many human rights defenders. Among the many things he has done, he is the author behind the picture of the still imprisoned Egyptian student Ahmed Samir Santawy we have used for our Egypt’s War Against Researchers: Giulio, Patrick, Ahmed and the Others, and the author of the iconic picture of Patrick Zaki, now finally free after 22 months of detention in Egypt.

Starting from a classical approach to art, Costantini developed an interest in comics and calligraphy through the years. By traveling to Sarajevo, through the works of the comics journalist Joe Sacco and others, but most notably Ernst Friedrich’s shocking photographic book, War Against War!, Costantini understood the importance of using visual art and clear, short captions as a way to move people to act. His artistry and his activism combined, and he developed his own style of capturing a story with just a few words and a drawing, becoming the human rights and political artist we know today.

Through the years he has collaborated with ActionAid, Amnesty, Emergency, ARCI, Oxfam Italy and many more organizations. His drawings have appeared at the HRW Film Festival in London, the FIFDH Human Rights Festival in Geneva, the Human Rights Festival of Milan and the International Festival in Ferrara. Since 2016 he has drawn for DiEM25 Democracy in Europe Movement 2025, a political movement founded by the former Greek Minister of Finance, Yanis Varoufakis. Among his most famous artistic collaborations there is the one with Ai Weiwei.

He has published comic stories on several outlets in his native Italy, such as Internazionale, Pagina99, “D la Repubblica”, “Narcomafie”, Corriere della Sera, and elsewhere, from Turkey, to France, where his work has appeared on the Courrier International and Le Monde Diplomatique, to the US, and Australia. He collaborates with the US information portals CNN, Words Without Borders and Muftah Magazine, The New Arab and the Dutch Drawing the Times. He also contributes to the Italian newspaper Domani. His latest books are Patrick Zaki, Una Storia Egiziana, Libia, Fedele alla linea, Diario segreto di Pasolini, Pertini fra le nuvole, Arrivederci Berlinguer, Cena con Gramsci, Julian Assange dall’etica hacker a Wikileaks and Cattive abitudini, L’ammaestratore di Istanbul,Bronson Drawings, Officina del macello and Le cicatrici tra i miei denti.

In 2017 he was nominated for the European Citizenship Awards. In 2019 he received the Art and Human Rights award from Amnesty International.

***

How did you start making art and what prompted you to devote yourself to illustration, and human rights as a theme?

I started very young, at the end of high school, then I went to the Academy of Fine Arts in Ravenna and already around the second year I started publishing illustrations and comics. In truth, initially, the choice was also very economical, I come from a working-class family, and I had very little money and comics were the poorest art and the one that would have given me more opportunities. You just need a sheet of paper and some black ink and you are ready to go. In those years I began a very aesthetic and decorative, almost mystical research. Lately, I’ve been collecting a few things on my channel.

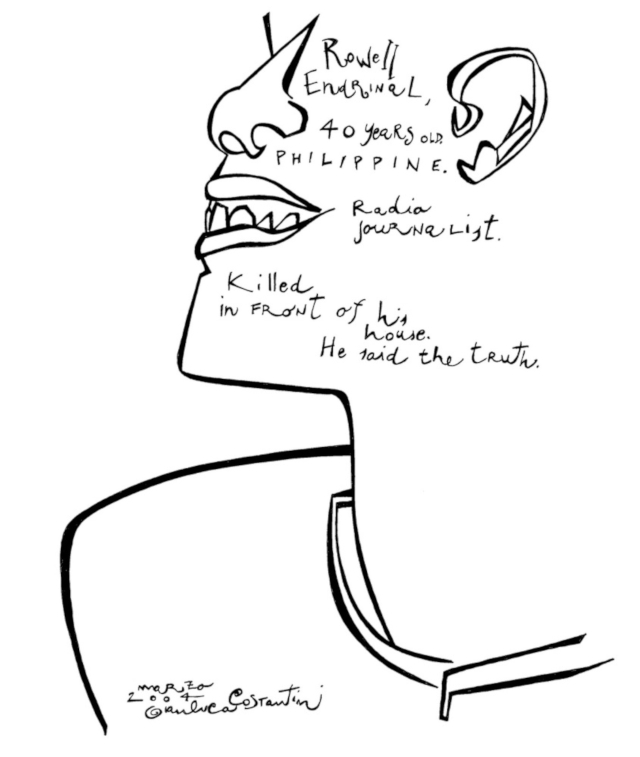

After about ten years, even if everything was going well, I was publishing and doing exhibitions, I began to feel a desire to leave the studio and tell the world, but to do this I had to revolutionize my way of drawing. I started to tell small facts from distant countries that attracted me, one of the first drawings was a journalist killed in the Philippines, Rowell Endrinal.

I began to publish these drawings on Indymedia, a no global counter information portal that in the 2000s worked a lot to convey a certain type of message. Then I focused on the great street protests and got in touch with people thanks to the birth of Twitter. So, I followed the demonstration in Istanbul, Gezi Park, and collaborated with activists, those of Occupy Wall Street, of Tahrir Square, those of Hong Kong. But then, little by little, I always got closer to the single person, to the person whose freedoms were and are taken away. From there on I got closer and closer to human rights.

Do you think it is possible to reach more people through illustrations, or people other than those reached through different, more institutional, campaign communications?

In recent years it seems that drawing has a role in all of this, it communicates the most uncomfortable themes in a different and perhaps more empathetic way. Drawings, but also comics are very powerful in communicating especially on social media. Many campaigns that have used my designs have been successful and I am very proud of them. People stop their gaze. But perhaps it has always been like this, art has always been political, from the one used for propaganda to the one used during revolutions.

How do you think the symbolic representation of social issues impacts political action or political communication? Have politicians ever given you the idea of being involved in your work, to the point of being pushed to take a side?

It is a delicate issue, because politicians do not always show interest for social and humanitarian reasons, but rather just to ride the wave of certain news, in Italy and in many other parts of the world as well. Then there are countries where political art is attacked by power and often censored. Of course, I have dealt with many politicians who have turned out to be really involved in a certain campaign and who still continue to follow new cases. Often drawing can stimulate them.

Over the years, have you noticed that you “had” to portray different themes, or rather, from your point of view as an artist for human rights, have you noticed previously more silent violations or new types of violence?

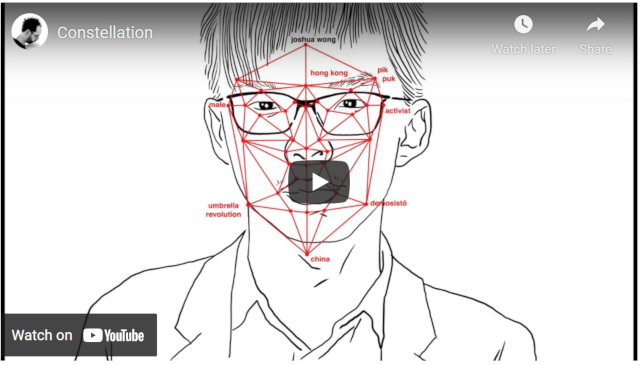

The themes change continuously, new conflicts or new freedoms arise every day. The subject of human rights is very broad and always opens up new themes. In recent years I have worked on some issues that are not very much listened to nor disseminated, but that are very important. Among these, I have been recently focusing on mass profiling and facial recognition.

A project by Gianluca Costantini

in collaboration with BBraio

Text by Arturo Di Corinto

Published on Wired Italia on 20 July 2021

Another topic that is very difficult to talk about is climate change, or if we want to talk about violence, what happens with femicide is perhaps the most silent violence of recent years.

Lately, have you noticed changes in the way people care about the world and the things they care about and have you changed your way of making art to make it more “effective”?

I believe that the changes in communication are continuous, even making a story on Instagram changes the perception of news and therefore we must try to adapt to the new media. As far as I am concerned, my work must always follow the trends, always be contemporary. If people change the way they talk and share news, my work must adapt to them. This is not due to a mere desire to be followed, but rather so that my work can still speak to the audience and progress. Otherwise, everything becomes repetitive and manneristic, while I want my art to be more and more effective.

Have you ever felt limited in doing your job because you feared censorship? Or have you been afraid that your work could bring you troubles, especially in recent years?

I have been subjected to a lot of censorship and intimidation. Some instances are very famous, such as the accusation of terrorism that the Turkish government accused me of in a trial in absentia in 2016.

Or when Steve Bannon accused me of anti-Semitism by getting me fired from CNN. But this happens when one’s work is infiltrated into reality and experiences the same dynamics. It means that my work is effective.

Can you tell us how you choose the people / themes to portray? Do people contact you or do you just draw and let your works find their audience?

After so many years of drawing, I am often considered a reliable and credible voice by activists from all over the world, so they often write to me asking me to follow a case by making drawings. I almost always say yes. Then there is my personal research that continues following the Twitter flows of what is happening in the world. Unfortunately, there is only the embarrassment of choice. The important thing is to make sure that the design works and for it to happen it is not enough to publish it, but you have to accompany it on the network, through the contacts with which you collaborate in order to amplify the scope of the message.

How do relationships with other artists arise, see Ai WeiWei, and how do they influence your work?

Usually, these relationships arise from mutual esteem, for a while we sniff each other on the web, then usually these connections blossom into an artistic or active relationship. With Ai Weiwei we started sharing our works with each other and then I started drawing him. He just liked this simple dynamic a lot. Then we did some more substantial work like when he invited me to Copenhagen to draw during a trial he had brought against Volkswagen.

Patrick Zaki. Could you tell us about your efforts in the campaign to free him and how your portrait of him has become so important to be used everywhere in these long months of his imprisonment?

It all started on 7 February 2020 when an anonymous activist wrote to me and said that an Egyptian boy who was studying in Italy had been arrested at the Cairo airport. The drawing that I immediately did was then the one that was used for almost two years. The drawing then became the image of one of the largest human rights movements that has ever occurred in Italy. In these two years, to keep the attention on Patrick’s case, I have created many public events and installations, such as the large drawing in Piazza Maggiore and under the Two Towers in Bologna, then the Zaki’s silhouettes from the University of Bologna went all over the place, and the kite with his cartoon has flown in many cities.

Is there a particular event that has impressed you positively and that has to do with your work?

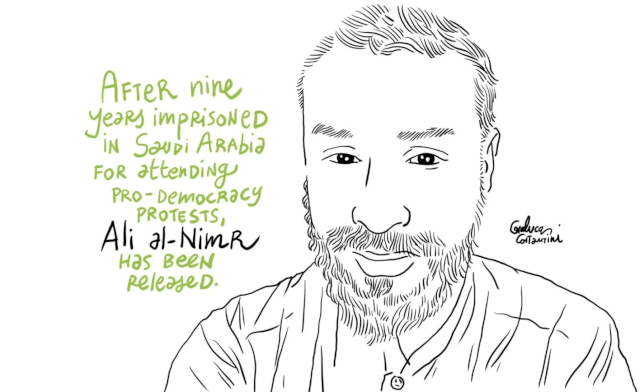

In the past 7 years, I have worked a lot on the case of a Saudi boy, Ali al-Nimr, who was arrested at 16 and sentenced to death. About two months ago he was released. It’s something I’m very proud of.

What do you think is particularly urgent today? What should people who choose policies that guide countries look at? What would you illustrate for them?

The most urgent issue is climate change which is directly linked to human rights, this is the main issue that should be addressed. In the near future, I will try to work a lot on this. We also need to help the kids who are working a lot on this theme. The other thing is to try not to lose those rights and freedoms we have gained, women’s rights in particular. But we also should care more about poor countries. All of these are very important and broad issues that seem not to touch us, but I am an idealist and I never give up, I am always convinced that things can improve. I do it with drawing, that’s what I do best.

You can find Gianluca Costantini’s work here:

http://www.channeldraw.org

Twitter

Facebook

If you want to sustain his work and let him be independent and free to create, you can support him via his patreon page.