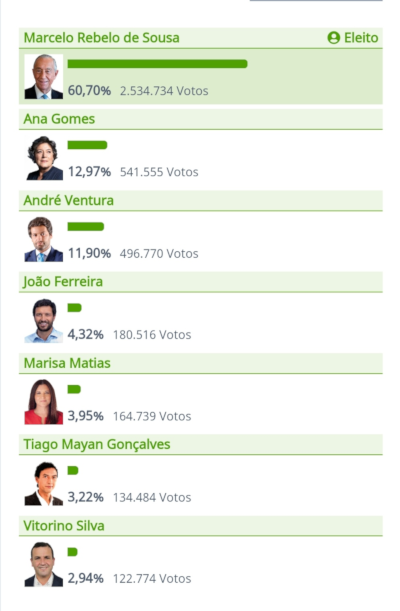

Despite the pandemic and the huge pressure on the health system, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa won the January 24 elections in the first round, as expected. He obtained more than 2.5 million or 60.7% of the votes, thus increasing his vote in relation to 2016. Marcelo had the declared support of the two right-wing traditional parties and the undeclared support of the socialist party. He was thus the consensual candidate of all parties in the “arc of governance”. He ran a completely personalised, non-partisan campaign focused on continuity.

Also, as expected, abstention rose to 60.5%. The trend of high and increasing abstention shows a general lack of legitimacy of the political system. However, in this case, abstention also increased by three other factors; the automatic inclusion of over one million voters abroad, the pandemic, which prevented a considerable part of the voters from participating in these elections, and the fact that this was a re-election with an almost certain result.

For the first time the extreme right, in the person of André Ventura, achieved a considerable result in presidential elections. Ventura focused his campaign on a crusade against "socialism", "corruption", "subsidy-dependents" and the Roma community. On January 24th he won almost half a million votes or 11.9%. Ventura and his Chega-party grew exponentially, following the 2019 legislative elections, when the extreme right had first entered parliament. Ventura used the campaign to create and strengthen the party at the national level, and to assert himself as political leadership of the radical right. Even so, Ventura failed to achieve all his own proposed (unrealistic) goals: to force Marcelo to a second round, being the second most voted candidate and to have more votes than all the candidates on the left combined.

Ventura fell short 1% to beat Ana Gomes. Without support from her own party (PS), Ana Gomes was still able to assert herself as the centre of opposition, not only against Marcelo, but also against the extreme right which she declared as her main enemy. Gomes - as well as the other candidates on the left - focused on the anti-social elements of the Chega programme such as the privatisation of the National Health Service and of education. Her campaign was also closely associated with the fight against anti-Roma racism - a fight that encouraged a large participation of people from the Roma community in her campaign and in the campaign against Ventura in general.

João Ferreira, of the Portuguese Communist Party, practically maintained the same number of votes as PCP candidate Edgar Silva in 2016. At the time, Silva’s campaign had been considered a disaster: it was the worst result ever for the PCP. Only in percentages, due to the greater abstention, Ferreira rose slightly compared to 2016. The PCP campaign had just one theme: defending the constitution – including the social rights it guaranteed. The mere defence of the constitution - however progressive it may be – is however hardly a strategy of alternatives. In the context of the pandemic, it lacked the potential to aggregate strata that have lost confidence in politics or those that revolt against the system. Tino de Rans, who as an independent, also tried to represent the same “ordinary working-class people”, also failed to capture the protest vote. With only 2,9%, he lost votes in comparison with 2016.

The biggest loser was the candidacy of the Left Bloc. Marisa Matias only had 3.95% of the votes, compared with 10.5% in 2016. Although Matias brought several important issues to the electoral campaign - including precariousness, requisition of private healthcare in the context of the pandemic, and her own personal campaign - especially because of health problems - fell far short of the 2016 result. This campaign was marked by direct confrontation with Ventura in the television debates. Various debates were marked by cheap insults, and Ventura - as a trained demagogue - emerged victorious. Ventura's macho insults regarding Matias' “red lipstick” in the debates, led to a wave of symbolic solidarity on social networks, recovered by the campaign under the slogan “red in Belem”. This certainly put Marisa and Ventura at the centre of the attention - but also took the focus off the rest of the campaign content.

Some on the left claimed that Matias' defeat was due to the “irresponsible” opposition of the Left Bloc regarding the last state budget. A left opposition is important, however, to have some left alternative to the crisis. This was confirmed by the polls. It is important to differentiate the rather personalized presidential elections from the more party-focussed legislative elections. In the legislative opinion polls – which showed no fundamental changes regarding the vote-intentions on the left side of the political spectrum if compared with the elections last year - BE kept stable around 7 to 8% of the votes; more than double Marisa's result.

The weak result of the presidential candidates on the left is partially explained by the concentration of their votes on the “lesser evil” figure of Ana Gomes; thus guaranteeing that a progressive candidate - nonetheless being a diplomat and Member of the European Parliament for the PS, closely linked to “the system” - had more votes than the extreme right. Another explanation is that Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa is seen, also among the traditional electorate of the left, as a warrant of continuity and stability in the midst of a pandemic. The majority support of the left electorate for the main candidates of the system, is a consequence of the left's inability to present a clear and credible alternative in relation to the management of the pandemic.

Although Marcelo was the centre-right candidate, he is associated with the PS-led government that many still consider "left-wing". This is what legitimised many people from the traditional left-wing electorate to vote for Marcelo. Polls showed that most of Marcelo's votes came from the left. It also explains the discontent of part of the PSD and CDS-base who decided to vote for Ventura – and to a lesser extent Mayan, the candidate of the new liberal party Iniciativa Liberal who got 3.22%.

The lack of anti-systemic opposition from the parliamentary left is also one of the factors behind the success of the extreme right. Until 2015, BE and PCP managed to raise social discontent and opposition to the regime based on progressive proposals. Upon entering into the governmental solution of Geringonça, however, they began to be “responsible” and to be part of the system, without presenting themselves as a fundamental alternative to neoliberalism and the consequences of peripheral capitalism: namely the problems of social inequality, a state of weak well-being and under attack, precarious work, massive emigration, low wages, dependence on the single currency, etc…

This factor is obviously amplified by the structural pre-existence of racism – not only towards its black population, but particularly towards Roma ,- and sexism present in the daily life of Portuguese society. It is enough to remember the continuous valorisation of the colonial past, the common practice of using “frogs” in commerce to keep gypsies away or the macho character of Portuguese justice since the “coutada do ibérico macho”. Until now, no political force had made an effective attempt to echo, strengthen and take advantage of this electorally. Ventura changed this and was highly effective in occupying this void.

A third factor is the crisis of the “democratic” right. Since the PS "dominated" the parties on its left for a more or less "good and responsible management"; that is, complying with international (neoliberal) agreements and rules on financial management, debt, and the protection of private initiative; the centre right had little room for criticism. The flight of their votes to the extreme right, and to a lesser extent to IL, has caused panic in the PSD and especially in the CDS. The right has reacted by trying to get closer to Chega - namely in the Azores government agreement - thus legitimizing the extreme right programme and discourse.

During the past few months, a new anti-fascist movement has emerged in Portugal, which, despite the pandemic, has managed to mobilise young people against the rise of Ventura. Hundreds of anti-fascists mobilized against the September Chega congress in Evora. More recently, during the election campaign, virtually all of Ventura's public rallies were the target of small spontaneous protests. The biggest mobilization took place in Coimbra, where anti-fascist groups, in just over two hours and in the middle of a pandemic, managed to mobilize almost 200 young people; effectively silencing and making Ventura's speech impossible in front of a mere 30 supporters. This achievement inspired a new protest - attended mainly by people from black and Roma communities - in Setúbal two days later. From then on, Ventura's campaign decided not to organise more public rallies. He accused - falsely - that the sabotage of his campaign was being orchestrated by the Left Bloc for electoral reasons. In another interview, he complained that anti-fascist actions made it impossible to have direct contact with the population.