In the age of fake news, environmental archives may provide crucial insights for political, legal and scientific controversies.

Berry pickers in the Pripyat Marshes near the Chernobyl Zone. Photo by Kim Trail.

Many people rejoiced at the end of the Cold War. It meant an end to threat assessments, a cessation of the build-up of nuclear weapons, an opening of borders and new connections bridged between East and West. But not everyone was thrilled. The end of the Cold War signaled a new set of “threats” for nuclear industries, especially in the United States. The threats were litigious in nature. As the Cold War creaked to an end, lawsuits sprang up. In the 1980s, Marshall Islanders – their homes blasted in nuclear tests, their bodies subjected to classified medical studies- went to court. Downwinders of the Nevada Test Site were lining up for lawsuits about cancer shadows in Utah and Nevada. The Metropolitan Edison Company in Pennsylvania faced plaintiffs living near the Three Mile Island nuclear power plant which suffered a partial meltdown in 1979. In the late 1980s, reporters and congressional investigators began to investigate US government agencies’ widescale engagement in human radiation experiments, including exposing tens of thousands of soldiers to nuclear blasts, injecting plutonium into hospital patients, and feeding radioactive oatmeal to orphans. These legal actions constituted an existential threat for nuclear industries, civilian and military. The Chernobyl accident exacerbated the hazards exponentially because the explosions in 1986 in northern Ukraine cast doubt on industry statements that nuclear energy is safer than coal, safer than flying or living in high-altitude Denver.

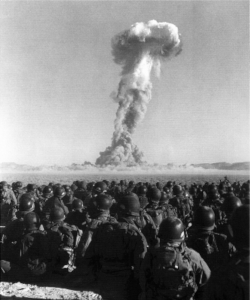

Nevada Test Site, November 2, 1951. Soldiers watching the Buster-Jangle Dog nuclear test, as part of exercise Desert Rock I. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Nevada Test Site, November 2, 1951. Soldiers watching the Buster-Jangle Dog nuclear test, as part of exercise Desert Rock I. Source: Wikimedia Commons

In 1987, a year after the Chernobyl accident, a group of scientists responsible for nuclear safety, health physicists, met in Columbia, Maryland, at the annual convention of the U.S. Health Physics Society. The conference’s keynote speaker came from the Department of Energy (DOE); the title of his talk drew on a sports analogy: “Radiation: the offense and the defense.” Switching metaphors to geo-politics, the speaker announced to the hall of nuclear professionals that his talk amounted to “the party line.” The biggest threat to nuclear industries, he told the gathered professionals, was not more disasters like Chernobyl and Three Mile Island, but “lawsuits.” After the address, lawyers from the Department of Justice met in break-out groups with the health physicists to prepare them to serve as “expert witnesses” against claimants suing the US government for alleged health problems due to exposure from government-issued radioactivity during the Cold War. The US Departments of Energy and Justice were prepping private citizens to defend the U.S. government and its corporate contractors as they ostensibly served as “objective” scientific experts in U.S. courts. In subsequent decades that strategy worked remarkably well. Health physicists took the stand across the country and insisted that plaintiffs’ doses were too low to have caused health damage. In the 1990s, they instrumentalized Chernobyl as a defense strategy. Pointing to U.N. assessments of Chernobyl consequences, they asserted that humankind’s worst nuclear disaster caused only 33 deaths. How could the much lower doses of radioactivity that downwinders received have triggered significant health problems? With such argumentation very few plaintiffs won in court, and the threat to nuclear industries passed.

Book cover of Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future (2019), W.W. Norton and Co

My book, Manual for Survival, came out in March 2019. The history documents the controversies over classified reports by Ukrainian and Belarusian doctors that people living in Chernobyl-contaminated territories were sick from a host of illnesses which doctors and residents came gradually to attribute to radioactive fallout from the accident. Once Soviet scientists were able to go public with their research in the late 1980s, international experts and leading scientists in the Soviet establishment attacked Soviet physicians, calling into question their expertise and authority, and generally maligning Soviet villagers as people who smoked, drank, had poor diets and so caused their own health problems. Scientists who did not submit were shouted down at conferences, slandered over coffee breaks and bodily removed from lecture halls. Some were fired. I thought I’d take a look at de-classified Soviet archives to see if I could figure out which side was right. After the Soviet Union fell apart, classified documents about the environmental and medical effects of the accident were released. I found thousands of pages of correspondence that amounted to a private conversation between Soviet authorities as they figured out the consequences of the disaster. Starting in Kyiv, I moved on to archives in Russia and Belarus. From central archives I worked down to county archives. Nearly everywhere I looked, I found a great deal of new evidence to support the Ukrainian and Belarusian scientists who spoke of a public health disaster. More controversially, I found U.N. archives revealed that a few key scientific administrators worked to dismiss or disappear evidence of the health crisis. These officials minimized and defunded U.N. organizations that tried to get to the bottom of reports of Chernobyl health problems. I reported these findings in my book.

The day after Manual for Survival appeared in print, social media around the book heated up. I became among some vocal critics a “fear-mongerer,” likened to “anti-vaxers and climate change deniers.” With broad brush strokes, an industry scientist and a pro-nuclear activist took to social media and the conventional media to discredit me personally as a way to dispense with the evidence and arguments in my book. I recognized the tactics—discredit, slander, minimize, while extolling the one truth of “experts.” It felt strange to be treated in a similar vein to characters I had written about in my book.

I learned how to respond to my critics on Twitter and in comment sections of newspapers. I grew a thicker skin. I did not doubt my research, however, because I had taken unusual measures to cross-check the documentary record. As I was researching, I understood that declassified Soviet archives would be questioned. The Soviet government was highly secretive and officials working for it had many reasons to mislead or deceive their bosses, especially when it came to public health. The Soviet mantra was that Soviet citizens were getting healthier and happier every day. A local sanitation doctor in territories contaminated with Chernobyl fallout had to have courage to report that more infants were dying than before; that they counted more respiratory problems, circulation disorders, anemia, thyroid conditions and cancers. I also understood that the documents were created during the last five years of the USSR, at a time of slow-motion political and economic collapse. Disgruntled employees had few resources to do their jobs. They earned little in reward for their labor and they might not have given much care to measurements and the charts they produced. Maybe the work was sloppy and ill-informed, as international experts charged?

Seeking to cross-check Soviet records, I turned to the landscape. People lie, I thought to myself, and archives lie, but what about pine trees? Two biologists, Tim Mousseau and Anders Møller had been working in the Chernobyl Zone for 15 years. I joined them on their annual trips, following them as a participant observer in their work which used the contaminated territories as a giant field lab. I also asked a forester to school me in the ecology of the Pripyat Marshes, where the accident occurred so I could get a ‘baseline’ of ecological health of the swamps. I began to understand how radioactive decay marks a landscape with its toxic fingerprint.

Pripyat river from bridge near Pinsk. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

I turned to oral history, contacting the few remaining medical doctors conducting research and treating people exposed to Chernobyl contaminants. I went to their clinics and to the villages where they worked. Using letters people had written in the 1980s complaining of Chernobyl health problems, my research assistants and I tracked down those residents and medical personnel 30 years later to hear their stories. I spent lots of time driving the lonely country roads of northern Ukraine and southern Belarus. I picked up women and children who were hitch-hiking. I did not report this in my book because it is anecdotal, but every rider I gave a ride to was traveling to or from a health clinic to seek help for the kinds of chronic health problems Soviet doctors reported in classified archives in the 1980s.

In short, as I reached for evidence outside the archive, especially environmental archives, I became more certain of the story declassified records laid out. I was able, effectively, to pick sides in an informed way. In this age of fake news, deep fakes, and highly politicized “experts” and information networks, turning to environmental archives, sources written onto human, animal and botanical bodies, helps us navigate around the political and scientific impasses that mark our modern age.

Kate Brown is Professor of Science, Technology, and Society at MIT. Among other books, she is the author of Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Future (2019), finalist for the NBCC award.

Original Contents by Undisciplined Environments