This article discusses intersections between sanitation, dignity and gender that are driving more expansive understandings of the human right to sanitation (HRtS), focusing on menstrual rights.

Definitions of sanitation as a human right are rooted in western international human rights law (IHRL). The HRtS is relatively ‘new’ human right with developing ´soft law´ norms under IHRL. See here for an overview of the HRtS. Concepts of claiming and attaining a HRtS are deeply intertwined with Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Target 6.2, which seeks, by 2030, “access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations”. The HRtS bisects social and cultural barriers and touches many aspects of our daily lives, linked by underlying determinants of health, human dignity and public welfare. In some ways, dignity provides a more compelling way of cutting through the technical, engineering and health frames linked to sanitation, to expose marginalisation and the day-to-day humanity around physiological sanitation needs.

Gender norms often drive discrimination regarding access to sanitation, which in different cultural contexts, are prevalent in peoples “access to safe and private sanitation facilities and the material resources to manage their menstruation” (Human Rights Watch, 2017, p.44). Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) is a “bedrock component of gender equality” and a “critical sanitation gap” (Burt et al., 2016, pp.5; 21-2). Furthermore, it is key to understanding the dignity aspects of the HRtS for people who menstruate1. Sanitation partly receives less attention than water due to the sensitive nature of toilets and a reluctance to talk about sanitation needs (Black & Fawcett, 2008, p.95). Added to this are societal gender norms that make discussion of menstrual hygiene a source of shame and embarrassment, ultimately restricting safe and secure access to toilets and failing to provide for menstrual hygiene needs (Cislaghi et al., 2018, p.7; UN Water, 2016a).

Human rights violations around menstrual hygiene include lack of access to hygiene products, stigmatisation and restricted movement imposed by family members during menstruation (Heller, 2019b). In parts of Nepal, the practice of Chhaupadi prohibits women and girls from participating in family life, sometimes exiling them from their homes during menstruation (Gates Foundation, 2018, p.11), restricting their ability to “access water or bathe, which can perpetuate poor sanitation and hygiene, increase risks of sanitation-related illness, and impact school or work attendance” (ibid). Furthermore, menstrual hygiene products are unaffordable for many. Stewart (2007) found that just two out of twenty menstruating school girls in rural schools in Zimbabwe could access disposable sanitary pads, with most relying on cotton wool, which increases risk of infection (Dengu-Zvobgo, 2004, cited in Stewart, 2007, p.301). Inadequate sanitation keeps girls from school and affects their ability to learn during menstruation (Burt et al., 2016, p.5), whilst Stewart (2007, p.294) notes a “profound silence around menstruation and its attendant management which affects some girls’ ability to function adequately in school”. The recent ‘cost of living crisis’ in the United Kingdom emphasises the high costs of MHM in the Global North. A WaterAid survey cited by Sky News suggests one in four UK women could not afford menstrual hygiene products, despite the government scrapping the ‘tampon tax’ in 2021. To bypass such taxes in Germany, The Female Company created The Tampon Book, which contains organic tampons disguised and sold in book form, in order to reduce the ‘luxury goods’ tax from 19% to a 7% ‘book’ rate.

A HRtS lens provides an entry point to increased menstrual hygiene-related rights awareness, helping normalise MHM provision in schools, in Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) policy and related development interventions. Furthermore, as Roaf and Albuquerque (2020, p.480) recognise, menstrual rights advocacy is expanding beyond the WASH sector, “which is essential to address the full range of human rights issues related to menstruation”. Critical Menstruation Studies are emerging as an important avenue of research that centres menstruation as a “multidimensional transdisciplinary subject of inquiry and advocacy” (Bobel et al., 2020, p.3). From a HRtS perspective, it is of immense analytical value in helping “reveal, unpack, and complicate inequalities across biological, social, cultural, religious, political, and historical dimensions” (ibid, p.4). For example, applying a Critical Menstruation Studies lens, Loughnan et al. (2020, p.578) analysed global efforts to measure and monitor menstrual health; emphasising that in addition to improving reproductive health, “overcoming menstrual-related stigma and ensuring that women and girls can manage their menstruation is key to achieving SDGs that touch on women’s and girls’ comfort, agency, participation, safety, well-being, and dignity”. The author’s note that no explicit reference to menstrual hygiene existed in any of the original SDG targets or indicators (ibid, p.580). To address this, the WHO/UNICEF-led Joint Monitoring Programme’s (JMP) SDG 6 monitoring sub-group developed monitoring indicators under an additional target: “By 2040 all women and adolescent girls are able to manage menstruation hygienically and with dignity” (JMP, 2016, cited in Loughnan et al., 2020, p.580).

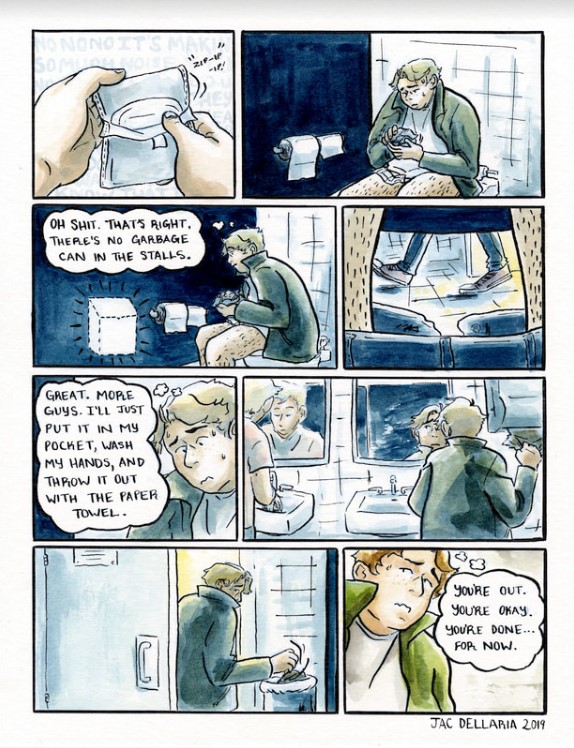

Intersectional understandings of the HRtS encompass gender needs and LGBTQI+ perspectives around menstrual hygiene. Discussions of gender and sanitation through a development lens have increasingly begun to recognise LGBTQI+ sanitation needs and human rights (Heller, 2019b, p.3; Yogyakarta Principle (YP) 14, 2006; YP+10 Principle 35, 2017). Some of challenges and misconceptions around MHM needs for people who menstruate, who may not identify as women or girls, are illustrated in a series of comic strips by artist Jac Dellaria (2019) in “Navigating the Binary: A Visual Narrative of Trans and Genderqueer Menstruation” (Frank & Dellaria, 2020, pp. 70-74 in Bobel et al., 2020). These comic strips illustrate: public bathrooms as sites of contested gender/sex identity in the context of menstruation; examples of trans and genderqueer fears and coping strategies for navigating binary bathrooms and MHM needs, (e.g. how stalls in men’s bathrooms rarely have waste bins for product disposal); the feminisation of menstrual products; and negative interactions with healthcare providers (ibid).

Artwork by Jac Dellaria (2019)

As reported by the Sanitation and Water for All (SWA) Secretariat on June 22, 2022, a recent meeting at the UN Human Rights Council (HRC) focused on increasing funding for menstruation-friendly sanitation facilities and tackling related gender-based discrimination. HRC Resolution 47/4 (2021) on “Menstrual hygiene management, human rights and gender equality” calls for removing or reducing sales taxes on tampons and pads, access to adequate sanitation facilities and investment in “publicity and awareness-raising campaigns to tackle stigma, shame, stereotypes and negative social norms”. As someone who has never experienced menstruation, I cannot speak to the myriad private and personal feelings, challenges and stigmas associated with MHM. As a human rights researcher, my PhD thesis ‘Data, Demand and Sanitation’ explores data gaps relating to demand for sanitation from a human rights perspective. This involves recognising that safe, healthy, affordable and dignified menstrual hygiene are critical to realising human rights.

Marcus Erridge is a PhD Student on the Human Rights in Contemporary Societies programme, CES, University of Coimbra. He holds a Masters in Understanding and Securing Human Rights (Distinction), Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London and has over 15 years of professional experience as an administrator, data analyst, and senior research associate for NGOs and educational institutions in the UK and US.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Notes:

1Where referring to the work of others regarding menstruation and sanitation, this researcher uses the terms and contexts intended by the authors, studies or laws cited, which are mostly presented in binary-legal gender terms, such as ‘women and girls’. Otherwise, the term ‘people who menstruate’ is used (Steele & Goldblatt, 2020, p.89, in Bobel et al. (Eds.), 2020).