Leslie Amine (Benin), Swamp, 2022.

Dear friends,

Greetings from the desk of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

In 1958, the poet and trade union leader Abdoulaye Mamani of Zinder (Niger) won an election in his home region against Hamani Diori, one of the founders of the Nigerien Progressive Party. This election result posed a problem for French colonial authorities, who wanted Diori to lead the new Niger. Mamani stood as a candidate for Niger’s left-wing Sawaba party, which was one of the leading forces in the independence movement against France. Sawaba was the party of the talakawa, the ‘commoners’, or the petit peuple (‘little folk’), the party of peasants and workers who wanted Niger to realise their hopes. The word ‘sawaba’ is related to the Hausa word ‘sawki’, meaning to be relieved or to be delivered from misery.

The election result was ultimately annulled, and Mamani decided not to run again because he knew that the die was cast against him. Diori won the re-election and became Niger’s first president in 1960.

Sawaba was banned by authorities in 1959, and Mamani went into exile in Ghana, Mali, and then Algeria. ‘Let us shatter resignation’, he wrote in his poem Espoir (‘Hope’). Mamani came home following Niger’s return to democracy in 1991. In 1993, Niger held its first multi-party election since 1960. The recently re-founded Sawaba won only two seats. That same year, Mamani died in a car accident. The hope of a generation that wanted to break free from France’s neocolonial grip on the country is expressed in Mamani’s stunning line let us shatter resignation.

Yancouba Badji (Niger), Départ pour la route clandestine d’Agadez (Niger) vers la Libye (‘Departure for the Clandestine Route From Agadez (Niger) to Libya’), n.d.

Niger is at the centre of Africa’s Sahel, the region at the south of the Sahara Desert. Most countries of the Sahel had been under French rule for almost a century before they emerged from direct colonialism in 1960, only to slip into a neocolonial structure that largely remains in place today. Around the time when Mamani returned home from Algeria, Alpha Oumar Konaré, a Marxist and former student leader, won the presidency in Mali. Like Niger, Mali was burdened with criminal debt ($3 billion), much of it driven up during military rule. Sixty percent of Mali’s fiscal receipts went toward debt servicing, meaning that Konaré had no chance to build an alternative agenda. When Konaré asked the United States to help Mali with this permanent debt crisis, George Moose, the US assistant secretary of state for African affairs during President Bill Clinton’s administration, replied by saying ‘virtue is its own reward’. In other words, Mali had to pay the debt. Konaré left office in 2002 bewildered. The entire Sahel was submerged in unpayable debt while multinational corporations reaped profits from its precious raw materials.

Each time the people of the Sahel rise, they have been struck down. This was the fate of Mali’s President Modibo Keïta, overthrown and jailed until his death in 1977, and the great president of Burkina Faso Thomas Sankara, assassinated in 1987. It is the sentence that has been levied against the people of the entire region. Now, Niger is once again moving in a direction that France and other Western countries do not like. They want neighbouring African countries to send in their militaries to bring ‘order’ to Niger. To explain what is happening in Niger and across the Sahel region, Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and the International Peoples’ Assembly present red alert no. 17, No Military Intervention against Niger, which makes up the remainder of this newsletter and can be downloaded here.

Why is there an increase in anti-French and anti-Western feeling in the Sahel?

From the mid-nineteenth century, French colonialism has galloped across North, West, and Central Africa. By 1960, France controlled almost five million square kilometres (eight times the size of France itself) in West Africa alone. Though national liberation movements from Senegal to Chad won independence from France that year, the French government maintained financial and monetary control through the African Financial Community or CFA (formerly the colonial French Community of Africa), maintaining the French CFA franc currency in the former West African colonies and forcing the newly independent countries to keep at least half of their foreign exchange reserves in the Banque de France. Sovereignty was not only restricted by these monetary chains: when new projects emerged in the area, they were met by French intervention (spectacularly with the assassination of Burkina Faso’s Thomas Sankara in 1987). France maintained the neocolonial structures that have allowed French companies to leech the natural resources of the region (such as the uranium from Niger, which powers a third of French lightbulbs) and have forced these countries to crush their hopes through an International Monetary Fund-driven debt-austerity agenda.

The simmering resentment against France escalated after the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) destroyed Libya in 2011 and exported instability across Africa’s Sahel region. A combination of secessionist groups, trans-Saharan smugglers, and al-Qaeda offshoots joined together and marched south of the Sahara to capture nearly two-thirds of Mali, large parts of Burkina Faso, and sections of Niger. French military intervention in the Sahel through Operation Barkhane (2013) and through the creation of the neocolonial G-5 Sahel Project led to an increase in violence by French troops, including against civilians. The IMF debt-austerity project, the Western wars in West Asia, and the destruction of Libya led to a rise in migration across the region. Rather than tackle the roots of the migration, Europe tried to build its southern border in the Sahel through military and foreign policy measures, including by exporting illegal surveillance technologies to the neocolonial governments in this belt of Africa. The cry ‘La France, dégage!’ (‘France, get out!’) defines the attitude of mass unrest in the region against the neocolonial structures that try to strangle the Sahel.

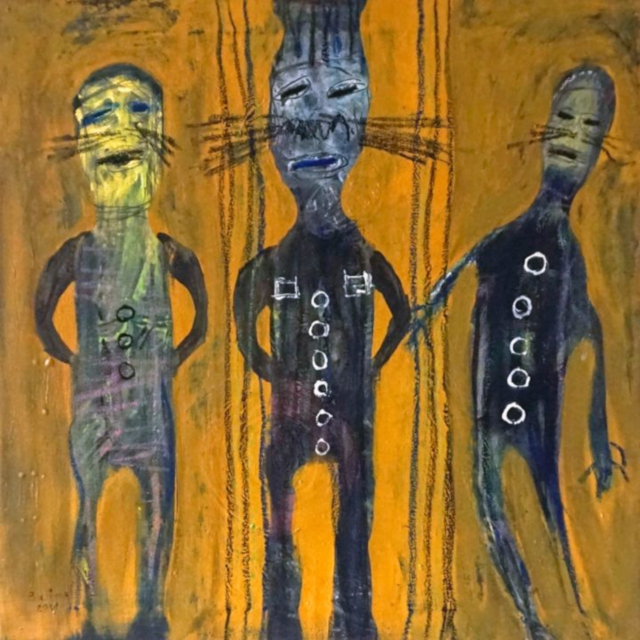

Wilfried Balima (Burkina Faso), Les trois camarades (‘The Three Comrades’), 2018.

Why are there so many coups in the Sahel?

Over the course of the past thirty years, politics in the Sahel countries have seriously desiccated. Many parties with a history that traces back to the national liberation movements and even the socialist movements (such as Niger’s Parti Nigérien pour la Démocratie et le Socialisme-Tarayya) have collapsed into being representatives of their elites, who, in turn, are conduits of a Western agenda. The entry of the al-Qaeda-smuggler forces gave the local elites and the West the justification to further squeeze the political environment, reducing already limited trade union freedoms and excising the left from the ranks of established political parties. The issue is not so much that the leaders of the mainstream political parties are ardently right-wing or centre-right, but that whatever their orientation, they have no real independence from the will of Paris and Washington. They have become – to use a word often voiced on the ground – ‘stooges’ of the West.

Absent any reliable political or democratic instruments, the discarded rural and petty-bourgeois sections of the Sahel countries turn to their urbanised children in the armed forces for leadership. People like Burkina Faso’s Captain Ibrahim Traoré (born in 1988), who was raised in the rural province of Mouhoun and studied geology in Ouagadougou, and Mali’s Colonel Assimi Goïta (born in 1983), who comes from the cattle market town and military redoubt of Kati, represent these broad class fractions. Their communities have been utterly marginalised by the hard austerity programmes of the IMF, the theft of their resources by Western multinationals, and the payments for Western military garrisons in the country. Discarded with no real political platform to speak for them, large sections of the country have rallied behind the patriotic intentions of these young military men, who have themselves been pushed by mass movements – such as trade unions and peasant organisations – in their countries. That is why the coup in Niger is being defended in mass rallies from the capital city of Niamey to the small, remote towns that border Libya. These young leaders do not come to power with a well-worked agenda. However, they have a level of admiration for people like Thomas Sankara: Captain Ibrahim Traoré of Burkina Faso, for instance, sports a red beret like Sankara, speaks with Sankara’s left-wing frankness, and even mimics Sankara’s diction.

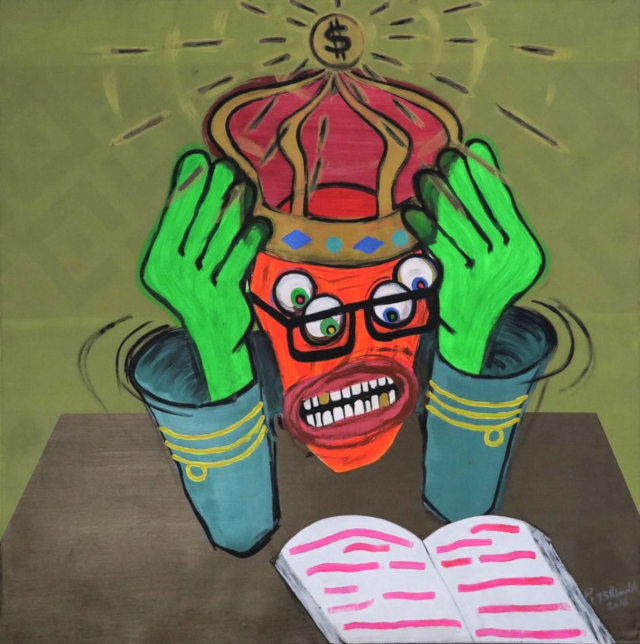

Pathy Tshindele (Democratic Republic of Congo), Sans Titre (‘Untitled’) from the series Power, 2016.

Will there be a pro-Western military intervention to remove the government of Niger?

Condemnations of the coup in Niger came quickly from the West (particularly France). The new government of Niger, led by a civilian (former finance minister Ali Mahaman Lamine Zeine), told French troops to leave the country and decided to cut uranium exports to France. Neither France nor the United States – which has built the largest drone base in the world in Agadez (Niger) – are keen to directly intervene with their own military forces. In 2021, France and the United States protected their private companies, TotalEnergies and ExxonMobil, in Mozambique by asking the Rwandan army to intervene militarily. In Niger, the West first wanted the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to invade on their behalf, but mass unrest in the ECOWAS member states, including condemnations from trade unions and people’s organisations, stayed the hands of the regional organisation’s ‘peacekeeping forces’. On 19 August of this year, ECOWAS sent a delegation to meet with Niger’s deposed president and with the new government. It has kept its troops on stand-by, warning that it has chosen an undisclosed ‘D-day’ for a military intervention.

The African Union, which had initially condemned the coup and suspended Niger from all union activity, recently stated that a military intervention should not take place. This statement has not stopped rumours from flying about, such as that Ghana might send its troops into Niger (despite the Presbyterian Church of Ghana’s warning not to intervene and the trade unions’ condemnation of a potential invasion). Neighbouring countries have closed their borders with Niger.

Meanwhile, the governments of Burkina Faso and Mali, which have sent troops to Niger, have said that any military intervention against the government of Niger will be taken as an invasion of their own countries. There is a serious conversation afoot about the creation of a new federation in the Sahel that includes Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, and Niger, which have a combined population of over 85 million. Rumblings amongst the populations from Senegal to Chad suggest that these might not be the last coups in this important belt of the African continent. The growth of platforms such as the West African Peoples Organisation is key to the political advancement in the region.

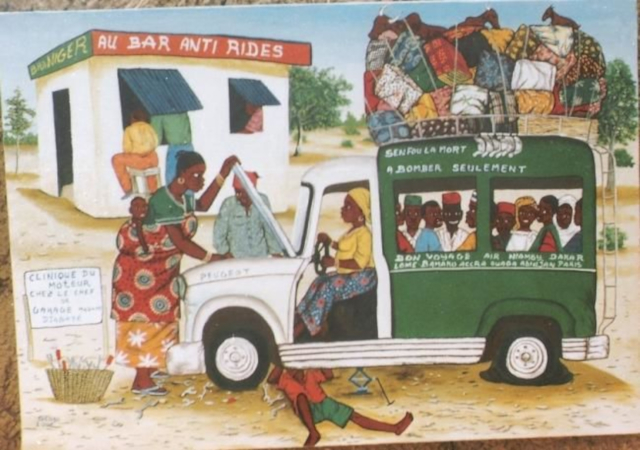

Seynihimap (Niger), Untitled, 2006.

On 11 August, Philippe Toyo Noudjènoumè, the general secretary of the Communist Party of Benin, wrote a letter to the president of his country and asked a precise and simple question: whose interests have driven Benin to go to war with Niger to starve its ‘sister’ population? ‘You want to commit the people of Benin to go suffocate the people of Niger for the strategic interests of France’, he continued; ‘I demand that… you refuse to involve our country in any aggressive operation against the sister population of Niger… [and] listen to the voice of our people… for peace, harmony, and the development of the African people’. This is the mood in the region: a boldness to confront the neocolonial structures that have prevented hope. The people want to shatter resignation.

Warmly,

Vijay

Original Contents by The Tricontinental