On a hot August day, I make my way to NYCHA’s Gowanus Houses in Brooklyn to attend the opening of “Undesign the Redline,” a national traveling exhibit on redlining created by designing the WE (dtW), a NYC-based design studio. The interactive exhibit explains how redlining, the once legal practice of systematically denying mortgages and other financial services to black and immigrant neighborhoods, baked poverty and social harm into those communities in a way that has yet to be widely understood, let alone undone.

.jpg)

Inside the Gowanus Houses community center, a handful of NYCHA residents and local activists have gathered for the opening. A portable air conditioner and a few standing fans are keeping everyone cool, but making it harder to hear. Karen Blondel, a NYCHA resident in the nearby Red Hook Houses and one of the community members trained by designing the WE to serve as a docent for the exhibit, is talking with two local police officers in front of a wall-sized “residential security map” of Brooklyn. Karen is explaining to the officers that as an area spirals down due to disinvestment, it becomes a place where police in trouble — officers who have psychological problems, get high, or deal drugs — are sent because what happens in redlined areas often stays below the radar. “I was asking them,” she tells us later, “to send us the good police.”

The map Karen and the officers were examining was created in 1938 by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, a federal housing agency that was part of the New Deal. Like a color-by-number painting, each section of Brooklyn has been assigned a color to show whether the area is “safe” for investment. Green means the area is a go for mortgages and loans. Blue and yellow get cautionary B and C grades. Red means the area is unfit for any kind of investment. In 1938, the only green neighborhood in Brooklyn is Bay Ridge. Almost all of northern Brooklyn, including Red Hook, Gowanus, and lower Park Slope, is shaded red.

The decision to draw a red line around a neighborhood, the exhibit explains, “was based almost entirely on race.” The language government and real estate publications use in the 1930s is eerily similar to the racist and anti-immigrant language we hear today. Surveyors are told to keep track of “any threat of infiltration of foreign-born, Negro or lower grade populations” and to estimate the likelihood of an area “being invaded by such groups.” Almost all the neighborhoods where “colored people” live are classified as “hazardous.”

At first glance, “Undesign the Redline” may seem bland — just a series of large red and white panels of text and pictures mounted on the walls. But the extraordinary thing about the exhibit, what really makes it pop, is that what’s on the walls doesn’t stay on the walls. Every time I’ve visited — the show spent a month on the other side of the Gowanus Canal before moving to the Gowanus Houses in mid-August — something interesting has been going on. Often it’s strangers striking up conversations with each other or with the docent on duty, but it’s also the rich programming which so far has included a neighborhood walking tour and discussion of Richard Rothstein’s The Color of the Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America. Local organizations, welcome to meet in the space, often break to view the exhibit.

“It’s really local folks who bring the exhibit to life,” Braden Crooks, a co-founder of dtW, tells me. “It’s not meant to be that we’re the experts coming in, and this is all the knowledge.” Instead, he says, the exhibit follows “a popular education model,” in recognition that “we all share that knowledge.”

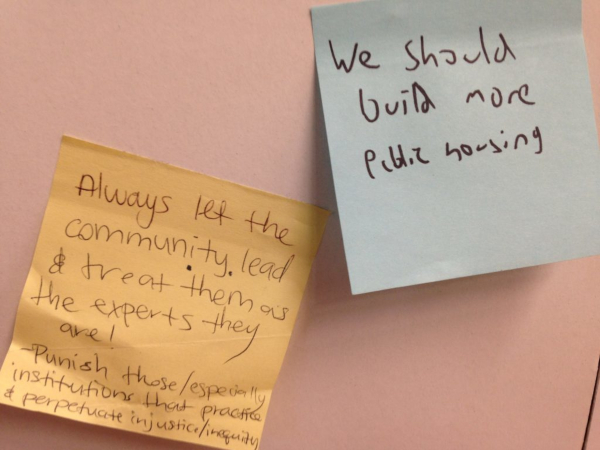

Fifth Avenue Committee (FAC), a community development corporation working in the neighborhood since 1978, has been the major activator of the exhibit in Gowanus. At the suggestion of dtW, FAC put together a community advisory board made up of local organizations and neighbors. That board met with dtW for several months with the result that local history, such as the building of the Gowanus Expressway and the creation of the Red Hook Community Justice Center, are included in the exhibit. One large panel is devoted entirely to local residents’ stories. Visitors to the exhibit can also weigh in by writing their thoughts or pointing out what’s missing on sticky notes and attaching them to the panels. Some of these ideas, Braden says, will become a part of future versions of the exhibit.

People who attend the exhibit are encouraged to share their thoughts via post-it note on how to end the harm caused by banks refusing to extend credit to people of color, a practice encouraged by the federal government for decades.

Redlining wasn’t taught when Braden was an architecture student. “It is not something that America really wants to talk about” he tells me. “Most people who lived through it, know it, but so many people have been totally isolated from that experience.” At the exhibit, you can see just how segregated our experiences are: some visitors express relief and a sense of validation because their story is finally being told, others shock and surprise because they “had no idea.” When Braden and dtW co-founder April De Simone started research for the exhibit in 2015, the only place they could view some of the 1930s redlining maps was in the National Archives. Now all of the maps have been digitized. Earlier this year, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago used those maps to examine the long-term trajectories of two areas that were statistically very similar before one was redlined. The study found lasting negative consequences for the redlined area.

The large central panel of the exhibit, an American history timeline which begins with the genocide of the Native Americans and comes up to the present, is filled with curving arrows showing connections between seemingly disparate events, movements and policies. The idea, Braden says, is to represent history “as a kind of cascade, one thing leading to the next. A lot of the ‘solutions’ of one era end up leading to the crises of the next era.” Redlining is a case in point: it was designed to help solve the 1930s foreclosure crisis by encouraging banks to give out affordable long-term mortgages to “stable” (i.e., white) neighborhoods.

The final panel in the exhibit takes up the question of what it would take to step off the merry-go-round of crisis-solution-crisis and solve problems in an antiracist and democratic way, driven from the grassroots and led by people in the neighborhood. This is not an academic question to the people who live in Gowanus. The city is proposing a rezoning of the area and, so far, many community members feel their input is being ignored. “This rezoning,” Karen tells me as we leave the exhibit, “could be another chapter in redlining.”

“Undesign the Redline” is at the Gowanus Houses community center through September. In October it moves to a tiny house in nearby Thomas Greene Park. For information about the exhibit, visit fifthave.org. For other venues in NYC or around the United States where “Undesign the Redline” is being shown, visit designingthewe.com.

Original Contents by The Indypendent